(ongoing, since 2022) — Documenting the resilience of migrant worker communities

An oddly placed Eiffel Tower in an unassuming village in Uzbekistan hints at a unique intersection of dreams and labor. Through both text and documentary photography, I track this confluence, as seasonal farmers craft homes and communities during their eight months working amidst the agricultural fields.

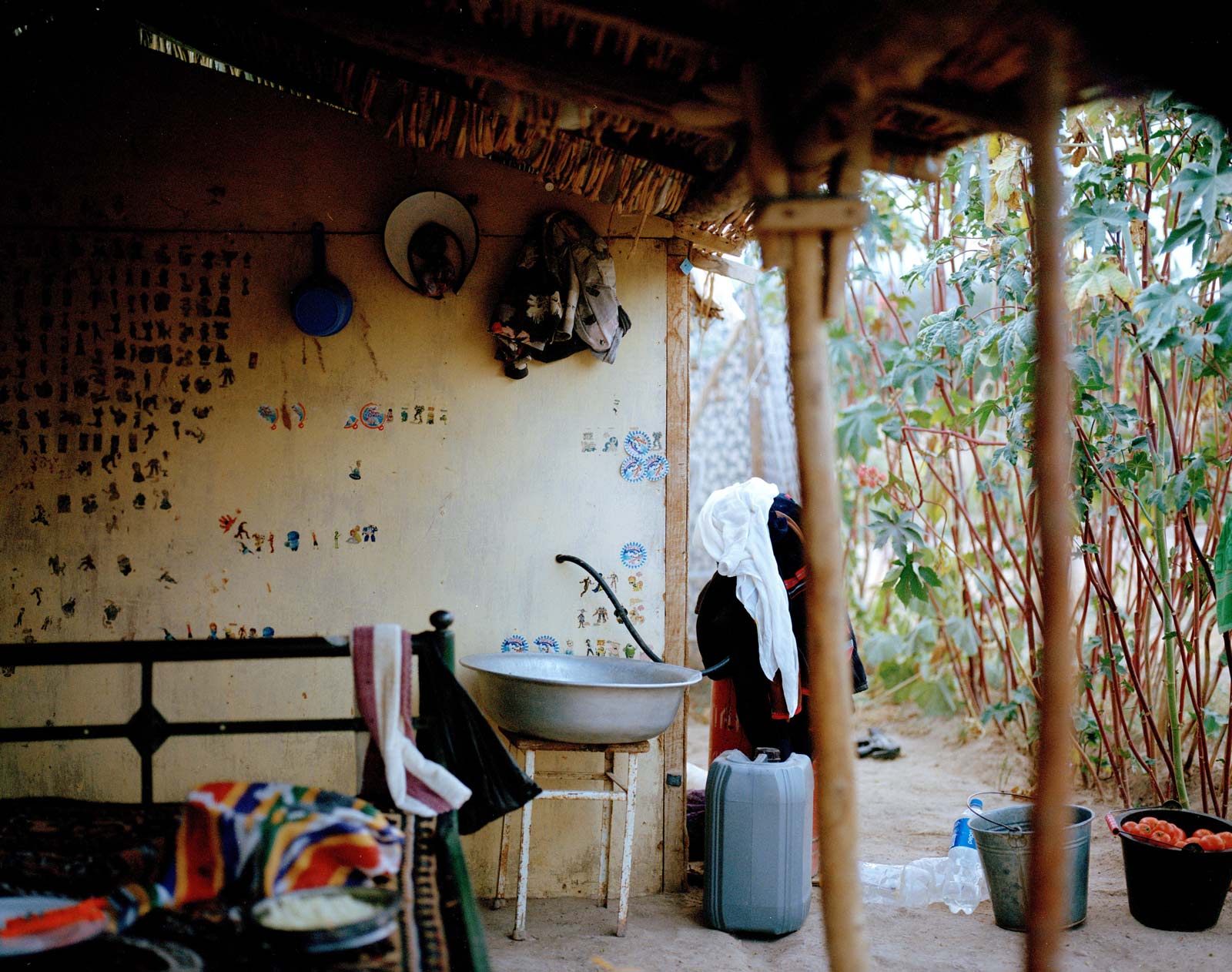

Farish in the Jizzak region of Uzbekistan is a somewhat magical place, where the Eiffel Tower («Farish» sounds almost like «Paris» in Uzbek and Russian) greets you at the entrance and where people build their own world that is not seen from outside. My project is a story of a large community of seasonal agricultural workers. For 8 months of the year, they live on the land of others with their whole families, build houses, work with their hands, grow tomatoes, melons and watermelons, raise their children, and watch Turkish TV series in the evenings. And then, for the winter, they go to their home in the east, to the Fergana Valley.

It’s a portrait of the spirit of seasonal farmers, who, in the face of challenging labor conditions, build lives marked by resilience and an unyielding sense of community. This project, at its core, is a tribute to these families who embody the heart and soul of Uzbekistan’s seasonal agriculture, their stories offering a poignant reflection of the country’s socio-cultural landscape and resisting the image of Uzbekistan portrayed on national television and Western orientalist misconceptions.

My far uncle’s (from grandma’s side) fields served as a stage for this project. In addition to my grandmother’s relatives, my grandfather was born there and lived there until he was 6 years old, until the war began. As a child, he often told us about this beautiful, blooming place, and I thought that my grandfather was so cool that he so often goes to Paris.

Farish is like Paris, Texas, only Paris, Jizzakh. The Uzbek dream is Paris. There are many replicas of the Eiffel Towers in various parts of Uzbekistan, it’s an obsession with Paris in some way.

In September/October the season is over and farmers go home. These transitional moments make me think a lot about what home means. How does it feel like when you’re not home all the time, or when your house fits in a truck? When you always live in a big community and they are your home? This story is just one of the many untold stories that, for me, constitute the real Uzbekistan. There is no place for the gloss and empty promises of the Yangi Uzbekiston from TV, but there is life in its great variety, warmth and connections.